Brave birds

The centenary of the First World War seems an appropriate time to reflect on the crucial role played by messenger pigeons, in what would have been terrifying surroundings for the birds. Their determination to get home undoubtedly served to save many lives.

The homing abilities of pigeons are uncanny, and even now, no-one is absolutely sure as to how they navigate back over large distances. It is believed that they rely on a combination of the Earth's magnetic field and their keen eyesight as they approach home, in order to detect familiar landmarks.

Pigeons were vital for communication purposes on battlefields for at least two thousand years, until the advent of satellite links. Indeed, it was only in the early 1990s that the use of messenger pigeons for military purposes finally ended. The last ones were kept in Switzerland, where a combination of high valleys and deep mountains meant that radio communications had always been difficult.

The unwavering determination of messenger pigeons under fire meant that help could be summonsed often against the odds, thanks to the remarkable abilities of these birds to continue to their destinations, even if they were badly injured. One of the bravest was Cher Ami, a messenger pigeon used in France by the American Expeditionary Force during the First World War.

On October 4th 1918, as the campaign was finally drawing to a close, an American unit found themselves trapped under heavy enemy shelling in the Argonne Forest area of north-eastern France. Reinforcements were urgently required, but the only means of communication with headquarters lay with the messenger pigeons.

German snipers, alert to this risk, had already shot down six birds immediately after they had been released. When Cher Ami was let loose with the vital message attached to his leg, he too was shot almost immediately, but he managed to fly on through a hail of bullets, some of which reached their target. One blew off his right leg, another severely injured his breast, and he was also blinded in one eye.

In spite of these appalling wounds however, Cher Ami was able to escape from the range of the guns, and reached the Divisional Headquarters with his vital communication, flying a distance of some 39km (24 miles) in just 25 minutes, so that help could be summoned for the beleaguered unit.

It was thought initially that Cher Ami was doomed to die, because of his dreadful injuries, but he was successfully nursed back to health. When the war ended, he was taken back to the USA in April 1919, after being presented with the French Croix de Guerre - one of the most significant awards for bravery. After his death, his body was preserved and it is now on display in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.. (Photo of Cher Ami seen above courtesy United States Signal Corps/Brianhe/Trizek)

Bravery recognised

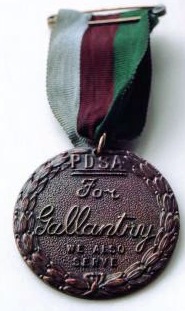

The so-called Dickin Medal, as shown here on the right, is often described as the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross (which is the highest award for bravery that can be awarded to British forces). It was conceived during the Second World War, being the idea of Maria Dickin, founder of the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals.

This well-known veterinary charity is much better known today simply as the PDSA and still occasionally awards the medal today, for 'conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving or associated with any branch of the armed forces or Civil Defence units."

Nevertheless, pigeons feature prominently in the list of animals to have received this award. The first three Dickin Medals, handed out at the end of 1943, were all given to pigeons. In fact, there were 54 medals awarded during the Second World War, with 32 of the recipients being pigeons.

It is easy to underestimate today just what vital roles pigeons played - not just as messengers, but also as morale boosters for the troops too. They were carried on planes, being released with the exact location if the crew had to ditch from the aircraft or the plane was forced down, thereby giving some hope of rescue.

In-bred determination

Even in peacetime, today's racing pigeons can face many dangers on their way back to the loft, ranging from attacks by peregrine falcons (right) to gunfire. During 1984, pigeon fancier Bill Shillaw, of Wentwork, South Yorkshire was alarmed when he heard shots being fired shortly after he had released some of his pigeons, including a bird called Cut-throat, on a training flight near his home.

Bill watched in horror as one of the flock fall from the sky, and a check on those that returned home safely revealed that Cut-throat who was missing. Having seen what happened himself, Bill was convinced that his beloved bird was dead.

He was therefore amazed when, a couple of days later, having gone down to the pigeon loft in his garden, he encountered Cut-throat, hobbling along with a badly-damaged wing. Instead of being able to fly back home, Cut-throat had made the journey on foot. The pigeon had travelled at least 3.5km (2ml) in this way, negotiating both open countryside and a fast road, escaping foxes, cats and cars, to arrive back safely at Bill's house.