The Catland Phenomenon

The rise of the postal service in the late 1800s saw British households typically receiving several deliveries a day, heralding a new era of communication.There was a growing demand for postcards, as a way of sending brief notes rather than more formal letters. Printing technology was also advancing quickly at this stage, with the use of colour illustrations starting to become commonplace.

It was a boom time for artists, in an era before the advent of colour photography, and with cats starting to become popular as household pets, so they were an increasingly obvious subject for such cards. Henriëtte Ronner (1821-1909) was one of the first to gain acclaim for her sympathetic paintings of cats, from the late 1860s onwards.

She portrayed them in a variety of domestic settings, often playing and sometimes standing. Her style (as seen on the right) was very authentic however, concentrating on anatomical detail which resulted in an almost photographic accuracy in the finished work.

The card boom

Gradually however, a more whimsical element entered the scene, initially thanks to Helena J. Maguire (1860-1909). Her work was published by Raphael Tuck and Sons from 1886 onwards, and although she did not actually dress her cats, they were often featured wearing bows. These cats also began to undertake a variety of 'human' activities as the years passed, such as mixing a Christmas pudding and even cycling.

Other artists were soon being commissioned alongside Tuck to meet the increasing demand for portrayals of cats. Notable among them was Louis Wain (1860-1939). When his wife became bed-ridden with cancer, the couple acquired a black and white kitten called Peter, and before long, Wain was sketching their pet. He was then commissioned to illustrate a children's book on cats, called Madam Tabby's Establishment.

His interest in cats led to Wain succeeding Harrison Weir as the second President of the National Cat Club during 1890. It was also at this stage that he began to devise the comical cats which were to become his trademark. The first example was published in The Illustrated London News newspaper in 1886, entitled A Kitten' s Christmas Party.

The anthropomorphic concept behind Catland - an essentially human world populated by cats - was already in place in Wain's mind when he undertook his first commission for Raphael Tuck in 1902.

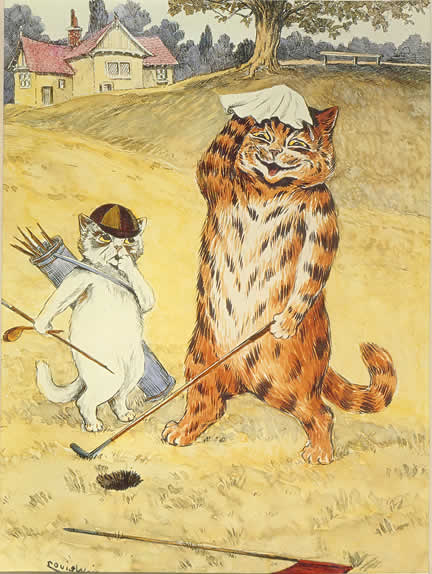

Other leading postcard publishers of this period also sought to profit from this trend as well. A whole world of cats dressed like people and carrying out a wide range of human activities, from skating to sailing and canoeing to canoodling, clearly struck a chord with a huge audience and sales boomed.

Although in almost all cases, these cats were shown wearing clothes and with accessories such as parasols, there was usually no attempt made to conceal their paws. They were rarely fitted with gloves or shoes, even though the consequences in this make-believe world could have been particularly painful, as in the scene “Paws before wicket” - a portrayal of cats playing cricket.

Seasonal events such as Christmas activities provided inspiration, and while there was no coherent theme revolving around individual cats, this highly distinctive style came to characterise Catland, which was a name coined by Wain himself.

Catland in decline

This fantasy world thrived for barely 40 years. Its decline was partly due to an increase in postal charges, which led to the subsequent collapse of the postcard industry, after its peak during the first decade of the 20th century. There was always an attractive naivety about the Catland characters, but the horrors of the First World War may also have led to a more cynical and hardened audience, which no longer succumbed as readily to their charm. By the early 1920s, the Catland era itself had essentially passed.

In the same way that technological change had led to its development, so further innovation almost certainly played a part in its demise as well. Perhaps surprisingly, there was no attempt to transfer the static images into the rapidly expanding field of film via cartoons, or develop any recognisable characters. Others, however, were not slow to exploit this expanding medium, including a young American called Walt Disney, whose Mickey Mouse went on to international stardom.

Wain himself (see here at work) tried to recapture the success of Catland in New York, but came back to Britain broke. He began to suffer serious mental health problems, which ultimately led to him becoming institutionalised on a paupers' ward in a London hospital. Influential and wealthy friends such as the writer H.G. Wells rallied round however, when they heard of his plight.

As a result, Louis Wain was ultimately transferred to a private hospital near St. Albans in Hertfordshire, where he spent the rest of his days. Here there was a colony of cats living in the grounds, and Wain continued drawing and sketching them, although his style had become very different. These cats were now portrayed in a much more abstract fashion, with bright colours predominating and flowers often incorporated into such pictures too, with no trace of anthropomorphism.

Collectible memorabilia

Cats have always been a popular subject with collectors. Henriëtte Ronner's work, with its emphasis on accuracy before the dominance of the photographic era, possesses a particularly timeless quality. Her originals sell for large sums when they come up for auction today, but it is also possible to purchase copies of her work as new greetings cards.

In the case of Wain's Catland images, these now appear to be coming back into favour, as part of a nostalgia boom. Not only are enthusiasts keen to add them to their collections of cat ephemera, with specialist dealers advertising such postcards in cat magazines and on the internet, but some of this work is also being reissued. It can often be found in shops offering reproductions of everyday items from the past.

Further proof of the revival of interest in the Catland era can be seen in the book field, with the publication of A Catland Companion, written by John Silvester and Ann Mobbs (published by Michael O'Mara Books), which gathers together many of the images produced by Louis Wain and other artists who were active in this sphere.

Photo from the book Louis Wain - The man who drew cats (ISBN 1-85479-098-6), courtesy of the author Rodney Dale.